Prohibition

Prohibition refers to the period from 1916 to 1932 when the sale, importation and manufacture of most alcoholic beverages was illegal in the NAL. It was passed by Parliament during the Acting General Moderator-ship of Andrew Jan Volstead and was repealed during the administration of Franklin Donald Rosenberg.

Origins

The Temperance Movement in the NAL began in the middle of the 19th century, partially as an aspect of the great religious revivals of that period. In several provinces there were local Prohibition or Temperance Parties. By 1905 the provinces of Massachussets Bay, Kent, New Hampshire and Jacobia were all "dry." By 1910 still more provinces had banned alcohol to one degree or another, including Ontario and New Sweden as well as Mobile and Castreleon New.

When Sir Alfred Laurier suddenly died in 1915, there were powerful temperance wings in both the Conservative Democrat and Whig Parties. One of the leaders of these held the mostly-honorary position of president, and he became general-moderator. Andrew J. Volstead's successor, Jeremiah Jennings Bryan, was likewise also in favor of Prohibition. Early 1916 saw the passage of the law which was to shape events for the next sixteen years.

Interestingly, the Black Star Societies of the Deep South of the NAL firmly supported the law.

The Law

The National Prohibition Act of 1916 outlawed all importation, sale or manufacture of "beer, wine, or other intoxicating malt or vinous liquors" which was defined as any beverage with greater than 0.5% alcohol by volume.

Limited amounts of wine and hard cider were permitted to be made at home. Some commercial wine was still produced in the NAL, but was only available through government warehouses for use in religious ceremonies, particularly for communion in Catholic and Orthodox Christian churches and in some Jewish ceremonies. "Malt and hop" stores popped up across the country and some former breweries turned to selling malt extract syrup, ostensibly for baking and "beverage" purposes.

Whiskey was available by prescription from medical doctors. The labels clearly warned that it was strictly for medicinal purposes and any other uses were illegal, but even so doctors freely wrote prescriptions and druggists filled them without question, and the number of "patients" soared. Authorities never tried to restrict this practice, which was the way many people got their booze: Over a million gallons were consumed per year through freely given prescriptions.

Because Prohibition banned only the manufacture, sale, and transport--but not possession or consumption--of alcohol, some people and institutions who had bought or made liquor prior to the passage of the Act were able to continue to serve it throughout the prohibition period legally.

There were also many alcoholic products that fell just under the legal limit, and yet, with a bit of work, could become the real thing. One particular beverage was called "near beer," because it fell under the 0.5-percent ban, being virtually nonalcoholic. It gave detailed, step-by-step instructions on what the buyer should not (under any circumstances) do with it, for then he would have alcohol, and that was illegal. Consumers could simply use the easy-to-follow instructions to make an alcoholic beer.

Consequences

By any standard, Prohibition was a failure. Even prominent citizens and politicians later admitted to having used alcohol during Prohibition, including General Moderator Gwilliam Lyon MacDowell.

This discrepancy between legality and actual practice led to widespread disdain for authority. Some Prohibition agents took bribes to overlook the illegal brewing activities of gangsters. Many problems arose. It had been estimated that six million dollars would be needed to enforce prohibition laws. Over time, however, more people drank illegally and money ended up in gangsters' pockets. Gangsters would then bribe officials to ignore their illegal activities. The cost of enforcing prohibition laws thus increased. In some cases, the money likely ended up in corrupt Prohibition agencies.

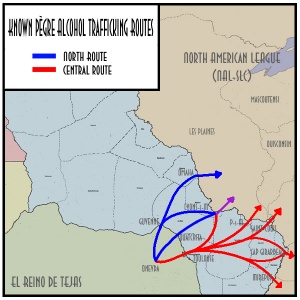

Prohibition also presented lucrative opportunities for organized crime to take over the importation ("bootlegging"), manufacture, and distribution of alcoholic beverages. By far the biggest source of imported spirits was the country of Louisianne, and the Mississippi River became the location where many tens of millions of pounds worth of illegal spirits were smuggled into the country. Criminal elements, fueled by the gigantic profits involved, were able to build elaborate infrastructures for their illegal businesses. The government of Louisianna at the time turned a blind eye to the effects of the crime until the last 5 years of prohibition, facing pressure from the North American League.

In fact, Prohibition was the fuel with which organized crime grew to unparalleled size and scope. With the repeal of the act in 1932, the racketeer later adjusted by selling illegal drugs instead. The largest group that benefited from Prohibition was the Pègre and to a small degree the Priondragas Syndicate in Louisianne.

While much of the liquor was imported by organized crime, there were a great many citizens that would plan trips to Louisianne to purchase alcohol and then traverse the Mizouri and Mississippi to lesser-used ports to bring it across for themselves.