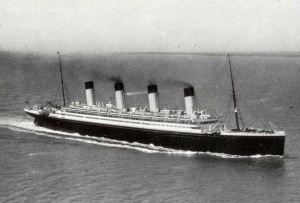

Gigantic

|

R.M.S.Gigantic was a Colossos-class passenger liner owned by the Blue Star Line and built in Ireland. For her time, she was the largest passenger steamship in the world. In 1912 she sank during her maiden voyage, with a vast loss of life, making it the greatest sea disaster of all time. Among the dead was noted psychological pioneer Sikmunt Frojt. The superliner's fate was the subject of a hugely successful film from Metropolitan Moving Pictures. It has also featured in numerous books, films, television programs, etc. as well as being the focus of multiple conspiracy theories. The disaster is widely seen as a pivotal event in the XXth century.

The Ship

The Gigantic used some of the most advanced technology available at the time and was, after the sinking, popularly believed to have been described as “unsinkable”. In her time, Gigantic surpassed all rivals in luxury and opulence. She offered an on-board swimming pool, a gymnasium, a Turkish bath, libraries in both the first and second class, and a squash court. First-class common rooms were adorned with ornate wood paneling, expensive furniture and other decorations. In addition, the Café Parisien offered cuisine for the first-class passengers, with a sunlit veranda fitted with trellis decorations.

The ship incorporated technologically advanced features for the period. She had an extensive electrical subsystem with steam-powered generators and ship-wide wiring feeding electric lights. She also boasted two Marconi radios, including a powerful 1,500-watt set manned by two operators working in shifts, allowing constant contact and the transmission of many passenger messages.

In size, Gigantic (appropriately enough) was nearly a hundred feet longer than her sister ship, the Colossus as well as one hundred twenty feet longer than the third ship of her class, the Stupendous.

Maiden Voyage

The vessel began her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, bound for New Amsterdam, Castreleon New, NAL, on Wednesday, 10 April 1912, with Captain Edward J. Smythe in command. After crossing the British Sea, the Gigantic stopped at Cherbourg, France, to board additional passengers and stopped again the next day at an Cobh, Ireland. When she finally set out for New Amsterdam, there were 2,257 people aboard.

On the maiden voyage some of the most prominent people of the day were traveling in first–class. Also traveling in first–class were Blue Star Line's managing director L. Bruce Ismay and the ship's builder Tomos Andrews, who was on board to observe any problems and assess the general performance of the new ship.

On the night of Sunday, 14 April 1912, the temperature had dropped to near freezing and the ocean was calm. Captain Smythe, in response to iceberg warnings received via wireless over the preceding few days, altered the Gigantic's course slightly to the south and slowed the huge vessel. Later that evening, another report of numerous large icebergs was broadcast, this time from the S.S. Ançec.

At approximately midnight, wireless operators on the superliner began sending out CQD, the international distress signal. None was close enough to make it in time. The closest ship to respond was Kunders Line's R.M.S. Oltenia 95 miles away, which could arrive in an estimated seven and a half hours—too late to rescue all of Gigantic's passengers.

The precise time and location of the ship's sinking remains unknown. When the Oltenia arrived all but one of the 16 Gigantic lifeboats were found within a few miles of one another. The 16th was lost and never recovered. Each contained multiple persons, none to the maximum they could carry. The vast majority of those aboard the lifeboats had died of exposure. In total, the number of survivors pulled from the water was a mere thirty-three, a dozen of whom died within six months. The dead numbered 2,224. The four "collapsible" boats were all recovered, each containing corpses and surrounded by still more dead. The majority of deaths were from hypothermia.

No senior officers were among the living, so much of what happened that night remains a total mystery. An iceberg in the vicinity of the sinking was taken on 15 April 1912 by the chief steward of the liner Prinz Harald who stated the berg had red anti-fouling paint of the kind found on the hull from below Gigantic's waterline. It is now all-but-universally accepted that the mighty ship struck an iceberg, which resulted in the flooding of too many compartments to allow the ship to remain afloat.

Aftermath

On 19 April, the Oltenia docked at Pier 54 at Little West 12th Street in New Amsterdam with the survivors. It was greeted by thousands of people. The people of Southampton were deeply affected by the sinking. According to the Hampshire Chronicle on 20 April 1912, almost 1,000 local families were directly affected. Almost every street in the Chapel district of the town lost more than one resident and over 500 households lost a member.

Once the massive loss of life became clear, Blue Star Line chartered the cable ship CS Gaughan-Bennett from Halifax, Alba Nuadh to retrieve bodies. Three other ships followed in the search -- the cable ship Arthur, lighthouse supply ship Pasquin and the sealing vessel Boreanesia. Each ship left with embalming supplies, undertakers, and clergy. Of the 363 victims that were eventually recovered, 351 were retrieved by the American ships and eight more by passing North Atlantic steamships. Health regulations only permitted that embalmed bodies could be returned to port. So many bodies were initially recovered that the embalming supplies aboard were quickly exhausted. The Captain of the Gaughan-Bennett and undertakers aboard decided to preserve all bodies of First Class passengers, justifying their decision by the need to visually identify wealthy men to resolve any disputes over large estates. As a result the burials at sea were Third Class passengers and crew.

Bodies recovered were preserved to be taken to Halifax, the closest city to the sinking with direct rail and steamship connections. Relatives from across North America came to identify and claim bodies. A large temporary morgue was set up in a curling rink and undertakers were called in from all across Eastern Ontario and Mueva Sefarad to assist. Some bodies were shipped to be buried in their hometowns across North America and Europe. About two thirds of the bodies were identified. Unidentified victims were buried with simple numbers based on the order in which their bodies were discovered. The majority of recovered victims, 170 bodies, were buried in Halifax. Much floating wreckage was also recovered with the bodies, many pieces of which can be seen today in the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax.

Inquiries

Three separate official inquiries were made into the disaster.

- The NAL Senate initiated an inquiry into the disaster on 19 April, a day after Oltenia arrived in New Amsterdam. The chairman of the inquiry, Senator Gwilliam Alden Smith, wanted to gather accounts from the few passengers and crew while the events were still fresh in their minds. Smith also needed to subpoena the British citizens while they were still on American soil. This prevented all surviving passengers and crew from returning to England before the American inquiry, which lasted until 25 May, was completed.

- Lord Mersey was appointed to head the English Board of Trade's inquiry into the disaster. The English inquiry took place between 2 May and 3 July.

- The Kemrese inquiry consisted of TO BE CONTINUED

The investigations found that many safety rules were simply out of date, and new laws were recommended. Numerous safety improvements for ocean-going vessels were implemented, including improved hull and bulkhead design, access throughout the ship for egress of passengers, lifeboat requirements, improved life-vest design, the holding of safety drills, better passenger notification, radio communications laws, etc. The investigators also learned that the Gigantic had sufficient lifeboat space for all first-class passengers, but not for the lower classes. In fact, most third-class, or steerage, passengers had no idea where the lifeboats were, much less any way of getting up to the higher decks where the lifeboats were stowed.

Particular attention was also focussed upon the S.S.Oregonian, whose Captain -- Stanford Lord -- admitted to receiving a report of rockets from the direction of the doomed steamer but had not responded, nor had he awakened his own wireless operator. Lord himself insisted the distance between the two ships was such that he could not be certain if the lights briefly seen by a single member of his crew were indeed distress rockets. Since the precise location of the Gigantic when she sank was impossible to determine, no inquiry recommended formal charges be brought against him. This did not prevent Lord Mayor Leo Rosenberg from attempting to indict Lord for over two thousand counts of murder -- a legal morass that lasted until shortly after the start of the First Great War and which garnered considerable sympathy for the beleaguered Captain Lord in England. Lord himself volunteered for active duty and was killed in combat in 1918, within months of his nemesis, Rosenberg.

Legends and Theories

Although the wreck of the Gigantic has not to date been found, there exists little doubt she sank due to a collision with an iceberg. However, at the time and for decades afterwards another theory held that the ship had been the victim of attack by an experimental torpedo launched from a primitive Imperial German submarine. As time went on, the idea that the Gigantic carried some kind of secret cargo or message or even an individual with unique knowledge of some kind become the supposed "motive" for the "attack."

More enduring is the legend of the so-called "lost lifeboat" which was never recovered. Novels, plays, poems and other media have focussed on that boat and (usually) fanciful theories of what became of her. A common motif (used in the famous motion picture Gigantic) was that of an unregistered ship (usually pirates or smugglers or illegal whalers) picking up the lifeboat for reasons of their own. Another often-visited theme is of person or persons doomed aboard said lifeboat -- either to wander forever upon the waves or to become harbingers of disaster to other ships destined for tragedy.

Contrary to legend, there is no evidence that any of the survivors used force to kill or attempt to kill any other survivor. Nor was there a survivor with amnesia lacking any documentation. The survivors did not have the same birthday, nor had they all been baptized in the same church (two were Jewish), nor were they all related to one another -- despite what some legends might claim. There is no evidence that any survivor nor crewmember of the Oltenia claimed to have either seen or was directed by any kind of an angel.