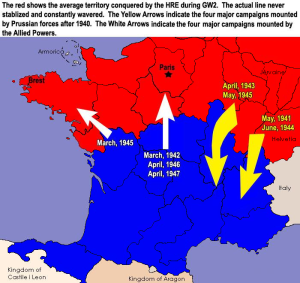

French Stalemate

The French Stalemate was the result of a clash between several different geopolitical/military facts:

- The Blitzkrieg, a new form of warfare in which the Holy Roman Empire's Wehrmacht operated in coordination with their powerful new Luftwaffe.

- Mobile Armored Artillery or "Tanks" (so-called in English because they were initially transported in boxes labeled such for security reasons during the First Great War). Whereas the Wehrmacht had developed the theories of Guderian to use Infantry as support for tank movements, the French had worked up essentially the same idea. Also, they had more tanks and troops (although their tanks were a notch or two below the German Panzers in quality). The point is that tank made trench warfare a thing of the past. And the two sides were fairly well balanced.

- Memory, and what was at stake. Both France and Hessler's empire wanted the French countryside intact. This, coupled with Hessler's desire for a negotiated peace with the Allied Powers, resulted in a de facto agreement on the Western Front not to engage in Total War. The French wanted their country back, and whole. The Empire wanted to keep the regions they'd conquered (or most of them) so were reluctant to ruin the prize for which they fought. This was also in keeping with Hessler's vision of war as a series of "surgical thrusts" rather than broad fronts.

The result of all this was a grinding series of battles of maneuver. Most of the front remained more-or-less stable, with skirmishes and raids SOP, but the focus of the conflict were specific campaigns designed to force the other side into an untenable position. Thus specific Armies would try--for example--to cut off France from Italy (this was tried twice) or to retake Paris (three times) or Brest (once) or to seriously threaten Avignon (twice).

It was a far cry from the blood baths that were the Eastern Front after Operation Rhinegold or the tortuous Balkan Campaigns. But it was a constant hemorrhage of supplies and manpower for much of the Second Great War.

The Maginot Line

The Maginot Line, named after French Minister of Defense André Maginot, was a line of concrete fortifications, tank obstacles, artillery casemates, machine gun posts, and other defenses, which France constructed along its borders with the Holy Roman Empire and Italy, in the light of experience from the First Great War, and in the run-up to the Second Great War. Generally the term describes either the entire system or just the defenses facing the Holy Roman Empire, but can be extended to include the fortifications made along the border of the French-Jervan Condominium, under Jervan auspices and those of the Batavian Kingdom, Het Verdedigingswerklinie. All were meant to repel any aggression from the Holy Roman Empire. France constructed a secondary line just west of their shared border with the Batavian Kingdom, knowing well that Adolf von Hessler and the Hohenzollerns had long eyed the Batavian Kingdom as a prize to be won. The Batavians were also aware of this, creating their fortifications of which the strongest point was Fort Eben-Emael. The Germans broke through exactly at this fortified point by airborne assault, against which the fortifications had little defense, which made it possible for them to invade France.

It was hoped that these fortifications would provide time for the army to be mobilized in the event of attack and/or to entice the Holy Roman Empire to direct its attentions elsewhere to avoid a direct assault on the line. The success of static, defensive combat in the First Great war was a key influence on French thinking of the time.

The fortification system successfully dissuaded a direct attack. However, it was an ineffective strategic gambit, as the Germans did indeed invade Batavia and Jervaine, flanked the Maginot Line, and proceeded relatively unobstructed to capture most of Francie.

Many historians credit the Maginot line with providing sufficient time to mobilize the army and enable the Stalemate, which was largely without loss of civilian life, something unheard of in most modern warfare.

The Alpine Pinch (1941)

In May of 1941, Adolf von Hessler launched the first German offensive to divide Italy and France. It was his hope that this would cut the mutual aid to both countries, as well as supply the German armies with a Mediterranean sea-port to further his objectives.

The Alpine Pinch pushed with ease from the launch-points of Geneva and Vevey on the opposite end of Lac Léman, but in battles at Bonneville, Annecy, Aix-les-Bains and Chambéry, the Germans were dealt heavy blows, with the French adopting a Russian tactic of falling back. The tide of the campaign, however, didn't turn until the battle of Grenoble, where German forces became embroiled in trench warfare and entrenched artillery high on the mountain slopes above Grenoble. It was only in the first days of the Isère Imbroglio at Grenoble that the Germans realized the battles fought en route to Grenoble had been diversionary tactics to keep them from reaching the Grenoblois fortifications before they were ready.

The Battle for Grenoble

The three week Battle for Grenoble proved to resemble the French Stalemate in microcosm, as the French forces and German forces exchanged blows up and down the long valley to the East of Grenoble. The end result was the defeat of the German forces who retreated to their territory in Helvetia by way of Voiron, where the final battle of the Alpine Pinch was fought.

The Parisian Offensive, 1942

In March of 1942, the French armies launched an assault to retake Paris, and thus cut the German supply lines to Brittany, facilitating the recapture of much of Francie, with great loss of munitions and man-power to the German Army.

to be expanded

The Avignon Thrust of 1943

The German leadership took to heart the successful decapitation of Francie's governing body with the capture of Paris in 1940. The attack toward Avignon was intended both to secure a Mediterranean naval base but also gut Gaulhe's governability with the capture of Lyon and Avignon.

to be expanded

The Second Alpine Pinch (1944)

Reconnaissance had lead the Germans to believe that the French army was lacking in munitions and manpower by early May of 1944, and so they began massing their troops in Geneva, Helvetia to attempt a second time to pinch the connection between France and Italy, and secure the port of Marseilles as a naval base.

Historians now blame much of the dysentery and other health concerns that crippled the German thrust on the cuisine that they were exposed to in Geneva.

to be expanded

The Breton Expedition

France wished to open a beachhead in Brittany for NAL-SLC and Louisiannan forces, and in March launched an offensive to capture Brest and Brittany and end the stalemate.

to be expanded

The Avignon Thrust of 1945

While the French Army was embroiled in the conflict in Brittany that had started in March, the Germans sought to launch a second offensive in May, opening up a two-front war for the embattled French, and hopefully bring the whole of France under German control, and at last gain the elusive Mediterranean naval base that would bring much needed fuel to the petrol-starved German war machine of western Europe.

to be expanded

The Parisian Offensives, 1946, 1947

Energized by the rout of German forces near Avignon the year prior, the French decided to again try to recapture Paris in two offensives, those of April, 1946 and April, 1947.

The offensive of April, 1946 was a bust as the French supply lines were cut by enterprising German battalions and the final attempt in April of 1947 was ended just north of Vichy by the Luftwaffe.

to be expanded

Historical Conclusions

Many French and German historians view the Stalemate as a success for the citizens of France, although not one militarily in the classic sense of victory.

to be expanded