Yemens War

| Name(s): | Yemens War, Yemenite Insurgency |

| Start of hostilities: | March 1959 |

| End of hostilities: | January 1976 |

| Winning side: | Losing side: |

Thousand Emirates |  Yemenite United Republic |

Hijaaz |  Iraaq |

| Note: | The United Arab Republic (supporting the rebels) and the Federated Kingdoms (supporting the emirates) also participated but not until the final stage of the war |

| Resulting treaty/treaties: | |

| Major consequences: | Decrease of influence of Laicist left-wing Pan-Arabism, international spreading of khat consumption, world’s attention to children soldiers problem |

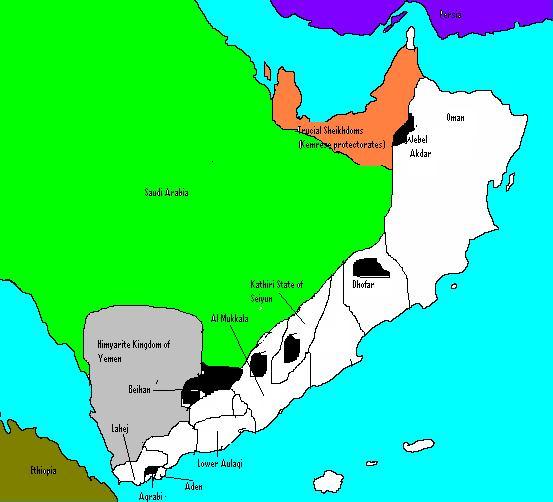

The Yemens War, also referred as the Yemenite Insurgency, was a war fought between 1959 and 1976. Combatants consisted of the Federated Kingdoms, several south Arabian states under English protection and the Hijaaz against a group of several pan-Arabist guerrilla movements supported directly by the United Arab Republic and Iraaq.

Backgound

In 1839, the English Royal Marines occupied the port of Aden at the south entry of the Red Sea founding the Colony of Aden. This colony became prosperous and gained much strong political and strategic importance especially after the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869.

Over the next decades England was able to convince the nearby Arab states to sign treaties of protection. These states feared a possible invasion by the Ottoman Empire as well as by the desert Bedouins led by the al-Saud family.

Relations between England and its south Arabian protectorates usually were friendly. England did not interfere with Arab internal politics and the Arab states avoided English affairs. While Aden prospered, most of the other Yemenite states were neglected and saw their economies stagnate.

All this changed with the Ethiopian Liberation War. In 1943, Ethiopia took control of Aden and established friendly relations with the emirates, which relied more for support on Ethiopia than on the Federated Kingdoms. But the Arab emirates were more interested in fighting each other in order to increase their area of influence than in international politics.

So, in 1944, the Emirate of Al-Mukkala took Aden from Ethiopia. Ethiopia recognised this power shift and signed a treaty of friendship with Al-Mukalla, which was at war with its neighbours.

With the end of the Ethiopian Liberation War the pre-war status was re-established, Aden returned to English hands and the emirates to English protection. Some Arab emirs were deposed.

In 1952, a young Egyptian general, Gamal Abdel Nasser, deposed the Khedive and established a republic. Nasser, a pan-Arabist, intended to gather all the Arab states into a union which would comprise one nation. The liberation of the foreign dominated Arabs became an important point of his international agenda. Among those he considered to be under foreign domination were the Arabs from the Yemens who were under English protection.

Despite Nasser’s troubled relations with the Federated Kingdoms some of the Yemenite emirs accepted Egyptian teachers and technicians during the 1950s in an act of “Arab solidarity” to help these poorer states to develop. But these teachers and technicians were often Egyptian intelligence and propaganda agents spreading pan-Arabist ideas according to Nasser’s philosophy. Many were expelled, accused of spreading subversion.

Encouraged by the nationalist rhetoric of President Nasser, movements soon arose intending to expel both the English and the traditional local leaders.

In 1956, the Federated Kingdoms were politically humiliated by not being able to defeat Egypt during the Suez Crisis. This gave even more strength to Yemenite nationalists. Even FK’s most loyal allies in the Middle East (the Hijaaz, Iraaq and Kuwayt) were rather critical of their war actions against Egypt. Relations between the FK and the Arab world suffered. In England First Lord Anthony Eden, who intended re-establishing friendly relations with the Arab countries, decided to transfer Aden to Arab rule changing its status from colony to protectorate, now the State of Aden. This and the other English protectorates in the Yemens were gathered into a new entity called the Federation of Aden on 18 January 1959.

Warfare

The Aden Emergency

In Aden such changes were ill-received by the English colonists. Violence erupted between the local Arab majority and the large English local community. A state of emergency was declared and the English army was sent to re-establish order, which was seen by the colons as treason. English and FK flags were burnt by angry colons and some, in an act of provocation, even sent a letter to the Ethiopian government asking it to take control of Aden.

By then the local English army garrison was rather reduced since Aden, now that it was a protectorate, it should be able to deal with its internal affairs, like the others. England in March 1959 asked Aden’s neighbouring state, the Sultanate of Lahej, for help in re-establishing order. Laheji troops entered the country on an emergency basis (thus the name Aden Emergency) which made the local rebelling Arabs consider the Federation of Aden just a puppet for the English government. For them Aden as a protectorate was not enough. They wanted full independence.

The Spread of the Guerrillas

Nasser, now also president of the new United Arab Republic (UAR), took the chance to spread his influence over the Yemens. Soon he sent funds, weapons and military advisors to the newly created liberation movements.

During May 1959 the Aden Arab nationalists and those from the neighbouring Aqrabi Sheikdom united and founded the Yemens Liberation Army and started a guerrilla war against the English forces and the emirate armies. Under the influence of the Nasserist ideal they soon adopted as a symbol the pan-Arabist colours: black, red, green and white.

In that same month other guerrilla movements all over the Yemens were formed and started their attacks against the established order: the Aulaqi Revolutionary Army in the Lower Aulaqi Sultanate, the Seiyun National Army in the Kathiri State of Seiyun (in the Yemens' hinterland) and the Saleh bin Ghalib Liberation Army in Al-Mukkala (taking the name of the emir who led the emirate during the Ethiopian Liberation War).

All claimed to follow in one way or another Nasserist pan-Arabism. All more or less presumed UAR help.

War internationalisation

In February 1960, Sharif Saleh al Hussein al Habieli, ruler of the Emirate of Beihan in the Yemens hinterland, was deposed and executed by the local Beihan Liberation Front which proclaimed the Yemens Arab Republic. The al Habieli family, related to the Hashemite, asked for help from the Hijaaz to restore the al Habieli rule.

With the acceptance of the FK government Hijaazi troops landed in the Yemens to provide military help to Beihan. This gave an excuse for Nasser to take more direct actions in the region. Soon the Yemenite rebels were joined openly by UAR troops.

Meanwhile in the Yemens Arab Republic reforms were made, inspired by Nasserite politics (land reform, education for children among others). The YAR looked for international recognition but the Arab Community, pressured by conservative regimes, denied any such claims. The only governments which recognised the YAR were the UAR and Iraaq under General Abdul Karim Qassim's rule, itself an internationally unrecognised government.

To help YAR, Qassim’s Iraaq sent also troops during that year and soon Hijaaz and Qassim’s Iraaq were fighting each other in Beihan.

The Yemenite United Republic

The existing four guerrilla movements united in July 1961 to form a new state which was called the Yemenite United Republic (YUR). Abdul Fatta Ismail, leader of the Beihan Liberation Front, was appointed president and Suq Abdulla, in Beihan, became the capital city.

The YUR’s structure was copied from the United Arab Republic. Each constituent, basically each territory controlled by each guerrilla, became a state with full internal autonomy but all co-ordinated in order to fight the “reactionary forces”. The YUR was then recognised by the UAR and Qassim’s Iraaq.

Life in the YUR was harsh. The constant state of war and isolation meant a poor standard of living. Even so the government tried to implement changes inspired by socialism. A literacy plan was established, lands were distributed among the people and a socialised medical system was created.

It was a highly militarised police state. The government controlled as much as possible and national security was used as an excuse for any and all human rights abuses. All capable men were drafted as soldiers whether they were supporters of the rebel cause or not. In some of the rebel-controlled enclaves children were drafted and fought as soldiers.

A national currency was created, the YUR dinar, and was pegged to the UAR pound. But the economy was nearly nonexistent. The YUR economical survival was almost completely dependent on funds sent by its Arab allies. Also the Red Crescent, Muslim branch of the Neutral Aid Society, regularly sent humanitarian support (food, medicines, etc.) in their own airships or those rented from neutral countries. As there was not a single aerodrome in the YUR, supplies were throw from the air.

The fall of Beihan and al-Shaabi’s rule

Syria withdrew from the UAR in early September 1961. Nasser soon after resigned and the UAR was dissolved. Both new powers in Egypt and Syria abandoned militant pan-Arabist polities and consequently stopped funding the YUR. Also their troops came back home. They had arrived as UAR citizens and returned as Egyptians or Syrians. The Arab Community provided them a safe passage to avoid their being captured as prisoners of war.

With less foreign support the YUR became even weaker. In December 1961, a joint force of Beihani royalists and Hijaazi troops reconquered Beihan. Abdul Fatta Ismail was captured and soon after, executed. Iraaqi propaganda made him a martyr of pan-Arabist cause and declared national mourning. In Beihan hijaazi troops remained at the emirate for years in order to protect it from possible new YUR attacks.

The YUR moved then its capital to Al Mukkala’s hinterland and appointed the leader of the Saleh bin Ghalib Liberation Army, Qahtan Muhammad al-Shaabi, as new president. Iraaq took then the complete responsibility for funding the YUR and provide them all possible help.

With al-Shaabi the YUR made some changes. Efforts were made to produce industrially a local drug, called khat, in order to provide YUR some extra sources of income. Through YUR’s embassy in Baghdaad contacts were made with several foreign criminal groups which helped the YUR to export khat outside the Middle East.

Later, from 1964 on, the YUR also started to raise funds through the printing of postage stamps. This was just a copy of what other emirates were already doing. These stamps, known as Yemenite rebel issues, were initially printed in the YUR but soon Iraaq and several neutral countries started to make their prints and distribute them. This caused the Yemens War to be known worldwide.

In 1964 the insurgency spread in Dhofar, eastern Yemens. A group led by Mussalim bin Nafli, the Dhofar Liberation Army, started hostilities and applied to join the YUR. In the next year Nafli’s troops also spread their rebellion into the Jebel Akhdar Mountains, close to the Trucial Sheikhdoms' border. But while these new fronts were added, the Aqrabi résistance pocket was taken by Lahej and Aqrabi royalists in late 1964.

The independence of the Thousand Emirates

In 1968 the FK announced their decision to end their treaties of protection in the Yemens. That would imply the independence of the whole territory and thus leaving the battlefield. The Yemens War was becoming too costly and long and public opinion had little or no understanding of what the FK (English more exactly) soldiers were doing there.

Knowing what such withdrawal could mean England also announced to the Yemenite emirs that support would be kept, not in men but in weapons and supplies.

Such independence could be considered as part of a strategy to take away the rebels' purpose. Also, apart some oil producing emirates plus Aden, all the other emirates were unprofitable and unimportant to English interests.

The Yemenite rulers understood that they should remain united to better fight the insurgency, and also to better face a possible invasion from their long-distrusted neighbour: Saudi Arabia. The Himyarite Kingdom of Yemen, an independent country of Jewish majority in the West Yemens, also decided to join the new confederation.

Yemens (the same as the geographical region) was supposed to be a good name for the new country. But for many emirs, wanting a decentralised government, it seemed too unitary and somehow pan-arabist. At the end the name Thousand Emirates was chosen, it would be royalist enough so as decentralised.

While the war was still going on the Thousand Emirates became independent on December 1971. Soon it joined the various international organisations while the YUR remained at that time just recognised by two countries, Iraaq and Qadhdhfi’s Libya (since 1970).

With independence FK troops left the territory leaving to the emirates the whole responsibility of their own defense and dealing with their own internal problems.

Final stage

On late 1973 the oil producing countries in general, and the arab ones in particular, were affected by a strong economical crisis caused by a sudden decrease on oil prices. It was the so-called Oil Crisis of Hijra 1393.

Both Iraaq and Libya were forced to make cuts in their support to Yemenite rebels. Both started to reduce their funds and Iraaq started also to withdraw its troops from the Yemens.

The YUR soon felt the impact and on April 1974 the rebel controlled area in Lower Aulaqi surrendered to the emirate army. Al Mukkala hinterland also fell, three months later, when the local population rebelled against the YUR due to harsh conditions and “President” al Shaabi (incapable to reach other rebel controlled areas) fled to exile in a same dirigible which was taking iraaqi troops back home. Last iraaqi soldiers left on September. The last funds and weapons were sent on December. From then on all iraaqi support was nothing more than rhetoric.

Now the YUR was just two enclaves, under the leadership of Mussalim bin Nafli. Without outside support the two enclaves had no connection between them and on January 1975 Dhofar rebels surrendered after a failed attempt to reach Jebel Ackdar through Rub al-Khali desert (the Empty Quarter) on which over half of the group died.

The last rebel pocket was now in the Jebel Akhdar Mountains, deep in Oman. The YUR was now reduced to a few valleys with no much water or grain. Due to its isolation and ground conditions Jebel Akhdar pocket was able to resist the omani army until January 1976. Omani army found then few dozens of skinny rebels desperate for water but it didn’t capture Nafli. He and some rebels tried to escape through the desert and died somewhere in the disputed area between the Thousand Emirates and Saudi Arabia. The rebellion was finally declared to be defeated although some isolated incidents took place as late as 1979.

Aftermath and war results

Despite being the longest conflict held in the Middle East during the twentieth century the Yemens War was relatively less bloody. Only English casualties are known to be sure (456 soldiers dead) and all the others’ figures are just estimates. It is calculated this war caused between 20,000 and 40,000 dead, mostly among the rebels or the emirates.

In terms of the region it eroded President Qassim’s authority in his own country, and contributed to decrease Nasserism as a mainstream ideology. The conflict also provided Iraaqi with military experience which would prove useful in the following wars caused by Sheik Hussayn regime. In the Thousand Emirates things went back to normal, with local traditional rulers having back their power without considerable changes.

Some historians consider the Yemens War helped to prevent larger and more deadly conflicts in the Middle East by making some of the regional most notable rivals (FK and the Egyptian-led UAR, Hijaaz and Qassim’s Iraaq) fight each other indirectly. In fact this was the only significant war set in the region between the Hajji War (1959) and the Persia-Iraaq War (1980-88).

In the world scene it was a war almost unknown and results were mostly social. It contributed to the spread of the khat consumption and dealing outside the Middle East and East Africa. In 1980 the Commission for World Health of the League of Nations recognised khat as a drug of abuse and since then many countries criminalized it or at least made restrictions on its use, possession and dealing although in some more liberal (especially the Batavian Kingdom) is freely sold. Still today some of the emirates, mostly in the western part of the Thousand Emirates, are accused for being producing khat for export and the local Yemeni Cartel is known to have connections with most of the other criminal organisations around the world.

Foreign Arab soldiers returning from war spread khat consumption in their own countries, first in Syria and Egypt and later in Iraaq and the Hijaaz. Since then khat became part of those countries youngsters' subcultures.

Movements for its legalisation worldwide appeared. “If tobacco and alcohol are legal why khat shouldn’t be?” they usually say.

This war also contributed to make the world wake up for the problem of the child soldier. In 1973 a photograph published by the ERA magazine showing a skinny dirty Yemenite boy with an old rifle executing a prisoner shocked the world. This photo became the best well known image of the Yemens War.

Weaponry

The Yemens War was almost totally fought on the ground. Among the emirates and rebels armies most of the weapons were old and outdated. This is partially explained by both the lack of local resources and the English polities which considered the emirates didn’t need modern weapons as “they were protected by one of the most powerful nations of the world”. FK didn’t forget that Aden have been taken by one of the emirates (Al Mukkala) during the Ethiopian Liberation War and especially since then wasn’t seen as convenient emirates to become too powerful.

Their mainstream weapons usually dated back the 1940’s at best although many weapons much older were reported. Motorised transportation was rare and among the emirates and rebels, motorised artillery and air means were perfectly unknown. Camels and horses were usually implied. The number of more modern weapons was small, even among the iraaqi-UAR-libyan backed rebels. A journalist described this war as “the last war of the 19th century”.

Only foreign belligerents had modern weapons. And only English and Hijjazi forces used air means for fighting. Both Iraaq and the UAR just used airplanes and dirigibles for transportation.