Assyrian Church

| Part of the series on Church of the East |

|

| Association |

| Communion of the Church of the East |

| Member Churches |

| Assyrian Church Borneian Church Religion of Light Chaldean Syrian Church Church of the East in Arakan, Burma and Tenasserim |

| Topics |

| Catholicos Assyrian Monasticism Assyrian Hospitals School of Samarqand Monastery of Mar Toma |

| People |

The Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East, to give it its full title, has a different and rather more illustrious history in Ill Bethisad than it does *here*, being as it is prominent in Central Asia, and also continuing to exist in parts of Persia, India and China, among other places.

See also:

Doctrinal and Liturgical Distinctives

Nestorianism

The Assyrian Church is often given the name Nestorian by outsiders; this refers to one of the early Christian controversies over how the divine and human natures of Christ fit together in the person of Jesus. See Wikipedia for a full account.

As a matter of record, the Assyrian Church itself rarely uses this label, preferring the term "Church of the East". As far as they are concerned, their doctrine descends directly from the Apostles, particularly Mar Toma (St. Thomas), Mar Tulmai (St. Bartholomew) and Mar Andir (St. Andrew), and they have preserved it intact ever since. The Church in the East refused to join in the condemnation of the highly-regarded Mar Nestorius, but they feel that the label "Nestorian" does a grave injustice to their doctrine as handed down from the apostles.

It should also be noted that Nestorius is perhaps the only church father condemned as a heretic by one of the early church councils who was not guilty to the heresy that bears their name. The Council of Ephesus (431) which condemned Nestorius was dominated by an ugly political quarrel between Nestorius and his supporters and Cyril of Alexandria, and the condemnation of Nestorius, according to the Church of the East, was politically motivated.

Saints and the Virgin

The Church in the East has a different understanding of sainthood than most of the Western churches. The Syriac honorific "Mar", often translated "Saint", is actually more literally "Reverend" or "holy one", and is used not just for the Apostles and Church Fathers, but for serving bishops and metropolitans and all priests of the Assyrian Church.

The use of this term illustrates the Assyrian understanding of the role of saints. In orthodox Assyrian teaching, one does not pray to a saint; a saint is an example, a leader to be followed, a model to look up to and try to emulate. This understanding is frequently modified by local popular religion, but in general, Assyrian Christians are more akin to Protestants in this regard - the grace of God is to be received through Christ in the Holy Qurbana (Eucharist), not through the mediation of some purely human secondary figure.

Similarly, although the Church of the East highly reverences the Virgin Mary, the title "Mother of God" is anathema to them. This was one of the main points of contention in the Council of Ephesus. To the Assyrian understanding, this title implies the blasphemous notion that Mary was the progenitor of the entire Godhead. They use the alternate title "Mother of Christ" instead. Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox Christians often feel that this implies the converse; that Mary's role as mother of the Christ only embraced His humanity, and that Christ was not God while in the womb of His mother.

These, and other theological differences remain unresolved between the Assyrian Church and other churches, and though in the last century there have been tentative steps made towards reunification with both the Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches, the fundamental doctrinal issues remain to be addressed.

The Liturgy of Mar Addai and Mar Mari

The standard liturgy of the Assyrian Church is known as the Holy Qurbana of Mar Addai and Mar Mari, or Holy Qurbana, an Eastern liturgical form that lacks the Words of Institution ("This is my body... This is my blood..."). It has been in continuous use by the Church of the East in this format without the Words of Institution since at least the VII Century. It exists in three forms: a simple, everyday form, a solemn form, and the most solemn form, known as the Raza. (See Wikipedia for further details).

Due to its lacking of Christ's institutional words, there is some controversy, particularly among Roman Catholics, as to whether the liturgy is a valid one. The Church of the East point out that they have their own long tradition to back up their practice.

The Liturgy may be said in either the vernacular or the Syriac tongue, depending on the level of solemnity of the service. The more formal the service, the more likely Syriac is to be used. Although most priests tend to use mostly the vernacular, certain portions of the anaphorae, for example, are almost always in Syriac.

Note: Learning the Syriac language is considered highly desirable for a would-be Assyrian ecclesiastic, especially as it is used as a common lingua franca in higher Church synods and gatherings. Many simple priests and monks, however, know little Syriac beyond the words of the Liturgy.

Melka: The Holy Leaven

Perhaps the most distinctive feature of the Assyrian liturgy is their use of the Holy Leaven, a tradition going back to the Apostles St. Thomas and St. Bartholomew, who committed into the keeping of the Eastern Church a sanctified leaven for making the bread for the Holy Qurbana. A portion of this leaven is used each time the Holy Qurbana is celebrated; if a church's supply should die, they must return to their bishop to gain a new portion. Nothing of this kind exists in the Western churches' liturgies, which raises the same kind of validity controversy for Assyrians that the lack of the Words of Institution in the Holy Qurbana raise for Catholics.

Priesthood and Laity

One of the things that has characterised the Assyrian Church of the East from a very early period right up to the present day is the high degree of lay participation. It was this, probably more than any other characteristic, that enabled the church's rapid spread into China and India, and enabled its continued survival among an at times very hostile Zoroastrian Persian Empire. All Assyrian believers, whether priest, monk, nun, trader, farmer or fisherman, would be involved in spreading the Gospel message and communicating their faith, and not just the "religious professionals" (priests and monastics).

This high level of participation of the laity necessitated a lay population well educated and versed in the Scriptures, in order to promote true understanding of the Gospel message and hamper the transmission of error. This has typically been the case. Assyrians have been involved in education and literacy since the IV Century and before; it is no accident that the ancient Sogdian, Uygur, Mongolian and Manchurian scripts all descend from the Syriac used by the Assyrian Church. It is interesting to note that when the Church of the East has historically neglected its education programs, a falling-away or downturn in membership has usually been the long term result.

A distinctive of the Assyrian priesthood is that they are permitted to marry. This was the result of a decision of the Synod of Beth Lapat in 484 AD. The actual attitude of the Church hierarchy to priests marrying has varied considerably over time, from being actively encouraged, through permitted but not encouraged, to permitted but actively discouraged and virtually disallowed. Currently, the Church permits its priests to marry if they so choose, but does not encourage this practice. Monks and nuns remain celibate since the Synod of Vagarshapat in 619 AD overturned the decision of Beth Lapat as far as its application to monks.

Hierarchy

The spiritual head of the Assyrian Church is the Patriarch of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, known as the Catholicos. Below him are the Metropolitans (archbishops), each overseeing between six and twelve bishops, with priests, monastics, missionaries and deacons under them.

It should be noted that the Assyrian Church is less hierarchical than the Roman Catholic Church *here*. The Catholicos of the Assyrian Church of the East is a position of "first among equals", with each Metropolitan more or less independent, but maintaining communion with others in the wider community of the Assyrian Church. Occasional Catholic Synods of all the (arch-)bishops of the Communion of the Church of the East reinforce the mutual ties between the sister churches in that communion, and more frequent Metropolitan Synods and General Synods of the Assyrian Church (of all the Metropolitans, and of all the bishops respectively) help maintain close ties, preserve correct doctrine and bring the collective wisdom of the Synod to bear on any larger issues facing the Church as a whole.

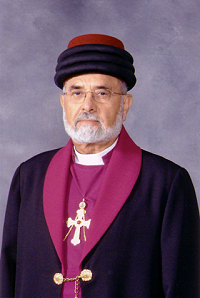

The ancient Patriarchal See of Seleucia-Ctesiphon is located on the outskirts of the modern Iraaqi city of Baghdaad. While technically a part of Iraaq, the Patriarchal See is fairly independent, and mostly manages its own affairs. The Iraaqi government fluctuates between trying to exert greater control on the Patriarchy and a more laissez-faire attitude, depending for the most part on the influence of its own Muslim hardliners. The current Catholicos is Mar Äbdiyeşü XVII.

Note on the title "Mar"

The Syriac honorific "Mar" is used in the Assyrian church to denote both priests and saints of the church. It is similar in essence to the Latin word "Sanctus" which became the word "Saint", meaning holy and revered. Thus the apostolic founder of the Assyrian Church is Mar Toma (Saint Thomas the Apostle), the Catholicos is Mar Äbdiyeşü XVII, and an ordinary priest might be Mar Sargis or Mar Nışdur or something similar. See also Saints and the Virgin above.

List of Metropolitan Sees

Those in italics are indigenous to IB.

In Persia and Mesopotamia

- Hawler, Kurdistan

- Azerbaijan, Persia (downgraded to Episcopal See)

- Bardaa, Persia (downgraded to Episcopal See)

- Basra, Al-Basra (resurrected in 2003 as an Episcopal See)

- Beit-Garmai, Thousand Emirates

- Halwan, Persia

- Jundishapur, Persia

- Karkh, Persia (extinct)

- Mosul, Iraaq

- Nisibis, Persia

- Rai, Persia - Metropolitan Mar Shimun Mertas

- Rewardashir, Persia

- Tabriz, Persia?

- Trablus, Lebanon - Metropolitan Mar Jebril ibn Dawoud

In Central Asia

- Atyrau, Qazaqstan

- Bayan-Olgii, Mongolia

- Buxara, Turkestan - Metropolitan Mar Gevärges

- Herat, Moghul National Realm

- Merv, Turkestan - Metropolitan Mar Zarafan

- Navekath, Moghul National Realm

- Qarağanda, Qazaqstan - Metropolitan Mar Qorbanjan Sargin

- Qaşgar, Turkestan

- Samarqand, Turkestan - Metropolitan Mar Qananıyeşü III

- Tara, Tocharstan

- Taraz, Turkestan - Metropolitan Mar Mertäs XIV

- Turfan, Uyguristan - Metropolitan Mar Tümütei VII

- Niislel Huree (Ulaanbataar), Mongolia

- Ürümçi, Uyguristan

- Xotan, Uyguristan (downgraded to Episcopal See)

In China

Most Metropolitan Sees in the Chinas are part of the Religion of Light Church of the East, however, there are two Sees in Tibet that are part of the Assyrian Church:

- Chamdo, Tibet - Metropolitan Mar Andra Timat

- Tangut, Tibet

- Patriarchate of Xi'an, Beihanguo (Headquarters of Religion of Light church)

See also Religion of Light

In India

Most Metropolitan Sees in India are part of the Chaldean Syrian Church, or of the Church of the East in Arakan, Burma and Tenasserim. The following are the independent Church of the East Patriarchates, and the few Metropolitanates of the Assyrian Church:

- Patriarchate of Akyab, Arakan (Headquarters of the Church of the East in Arakan, Burma and Tenasserim)

- Leh, Kaxmír

- Patriarchate of Mahe, Maisúr (Headquarters of the Chaldean Syrian Church)

- Mírut, Bháraþíj Sámrázj

- Patna, Ban̊gál

See also Chaldean Syrian Church

In Southeast Asia

Metropolitan Sees of Southeast Asia fall under the aegis of the Borneian Church

- Majaguru (Patriarchate} of Quinabatañgan, Bornei-Filipinas (Headquarters of the Borneian Church of the East) - Majaguru Alexander III

See also Borneian Church

In the rest of the world

- Constantinople, Greece (Assyrian Metropolitan of Europe) - Metropolitan Mar Gewargis Sabrisho

- Nome, Alyaska (Assyrian Metropolitan of the Americas) - Metropolitan Mar Samsoun

History

Early History

The Church of the East traces its origins to the Apostle Mar Toma (St. Thomas), as well as Mar Addai and Mar Mari, two members of the Seventy-Two lesser apostles. From the earliest days, the Church in the East was strong in the Persian Empire,and consequently held in some suspicion by the Sassanid rulers of Rome's greatest enemy, especially after the Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity.

In 424, a synod of all the bishops of the Persian empire declared the Eastern church in the Persian empire independent of the jurisdiction of Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria or any of the other Patriarchal sees, with the bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon equal in authority to any partiarch of the Western Church. Consequently, there were no representatives of this large body of the global Church at the Council of Ephesus in 431 which condemned Nestorius as a heretic, and the bishops of the Persian Church did not feel at all bound by the decisions of that council.

Nestorius' supporters were received as brothers by the Church of the East, and helped to bolster the church within the Persian Empire.

One of the early church controversies in the Church of the East was over the priesthood and celibacy. In the Persian Empire, the Zoroastrian faith places a very high value on family and the calling of parenthood, and particularly in this early historical period, the celibacy of the Christian priests was both bizarre and suspicious to the dasturs. In 484, at the Synod of Beth Lapat, the decision was reached that in order not to put a stumbling block before the Persians among whom so many lived and worked, it would be a valuable thing if the higher clergy were married. Indeed, the ruling of the Synod virtually required all Assyrian churchmen, both priest and lay monastic alike, to marry.

Following this ruling, it was eventually noted that the spirituality and theological depth, particularly of monks, was in decline. The tide began to turn again in 571 with the foundation by Abraham the Great of Qaşgar of a new monastery close to Nisibis, where the premier theological school of the Church was located. Abraham of Qaşgar's desire was to purify the monastic tradition and return to the high spirituality which had formerly characterised those of the monastic communities.

Also in 571, however, Henana of Adiabene became leader of the School of Nisibis, and began to depart from the historic theology of the Church, teaching instead the Neo-Platonic theology of Origen, and a divergent Christology owing more to Greek philosophy than to historic Christianity. Due to Henana's protection by the Persian Emperor, the Church hierarchy found it difficult to censure or restrain Henana, until the year 612.

In 612, Babai the Great became Catholicos of the Assyrian Church of the East. Like *here*, Babai was a scholar and theologian of the first rank; unlike *here*, the Persian rulers of the time were not able to block the election of a new Catholicos after the previous incumbent's death, and Babai was made Catholicos. (*Here* the office of Catholicos sat vacant for some time, and Babai retained his prior title of Visitor of the Monasteries of the North.) Babai the Great used his considerable influence to further the reforms begun by Abraham of Qaşgar. One of his first acts as Catholicos was to curb the influence of the dangerous Henana and his followers, though he would not succeed in actually removing Henana of Adiabene until 622. Babai's treatise on the two qnome (essences) unmingled but eternally united in the one parsopa (personality) of Christ eventually became the definitive Christological work of the Assyrian Church of the East.

Expansion

From the outset, the Church of the East was strongly missionary, and by the year 650, there were already Assyrian bishops in Central Asia, India, China and the Middle East. Assyrian monastic communities did a lot of the initial work; these were more similar to their counterparts in Kemr and Scotland than anything descending from the main Roman Catholic monastic tradition. An Assyrian abbey was a base of operations in the wider world, not a retreat away from it.

The Church in the East promoted study, literacy and learning; from its inception, the Scriptures were meant for the people, not just the priests. Whenever the church penetrated a new area, they would set up a library, a school, and a hospital to care for the sick.

Syriac was used as the main liturgical language; it was a common lingua franca in the northern and western Persian Empire where the Assyrian heartland was located, and the missionaries of the Assyrian Church took the language with them wherever they went.

However, unlike *here*, where Syriac was used almost exclusively, from the 8th Century there was a movement within the Church paralleling the physical expansion towards greater indigenisation. The Church synods began to push the idea of using local languages as the main liturgical languages, retaining Syriac for use in general synods and as a common tongue. The Holy Scriptures and other Assyrian books such as the Diatessaron (a harmony of the four Gospels) and the Liturgy of Mar Addai and Mar Mari began to be translated into the myriad tongues of the Assyrian community.

In some cases this meant the wholesale creation of a new script; the Sogdian-Uygur-Mongolian cluster of scripts (of which the Turkestani script Soğdo is a descendent) were all based on Syriac writing and were largely the work of Assyrian missionaries.

This indigenisation movement would be a factor in helping many of the Assyrian churches to survive later persecutions; in China and Central Asia the use of local languages and scripts helped to persuade later hostile governments that this was not just a foreign religion.

Persecutions and Survival

From its very beginnings the Assyrian Church was persecuted by its rulers: first by the Romans, then by the Persians, then by the Arabs. Unlike the Western church, the Assyrian Church of the East *here* never became really accepted by the secular powers who ruled over them, but remained a disenfranchised minority, at least in the Persian Empire.

*There*, at least one of the major persecution episodes was probably cut short, or didn't happen, and the Church was thus able to concentrate on more than just survival. During the ideological battles between Zoroastrianism and Islam within Persia, the Assyrian Church was able to grow and find its footing because it was considered by both sides to be less of a threat and problem than the other.

It was in Central Asia, though, that the Church was to really find open ground. For a while between the 11th and 14th Centuries, it looked as though the Assyrian form of Christianity would become the dominant religion of the region.

What happened to change this? In a word: Timur.

Timur (aka Tamerlane) was a Muslim. Up until his time Islam had been a very marginal religious group in Central Asia, especially further north into the steppes, where the religion had a very difficult time getting established. However, after the accession of Timur Islam became very much the preferred religious group. Initially at least, little actual organised persecution happened, but many politically ambitious people professed Islam in order to gain promotions.

It did not help matters that the Assyrian hierarchy was going through a weak period, having had a succession of corrupt or incompetent Catholicoses. These two factors combined to weaken the Church in Central Asia and drive the Chinese Religion of Light and Indian Thomist churches towards independence. In the Middle East, Timur's conquests were quite bloody, and according to Assyrian sources, he seemed to go out of his way to destroy the Assyrian Church in that region. Many of the ancient Assyrian metropolitanates went extinct at this time, and the few that remained were never again to reach the heights that they had before Timur.

The Modern Assyrian Church

The modern Assyrian Church is strongest in Central Asia and India, though it has dioceses and bishoprics all over the world. The current Catholicos is Mar Äbdiyeşü XVII, a Turkestani Tajik by birth.

Unlike *here*, the Assyrian Church never made its highest authorities (Patriarchal and Metropolitan sees) into hereditary positions; a new Metropolitan or Patriarch *there* is still selected on merit, as it were, upon the death of their predecessor.

Monasticism

Main Article: Assyrian Monasticism

An important current in the Assyrian Church is its monastic movement. Unlike some schools of monasticism in the Western churches (both Orthodox and Catholic), the Assyrian monastic school is one of engagement with the wider community at least as much as retreat away from it. Assyrian monastic communities were and are one of the first arms of the Church to enter a new area, so Assyrian monasteries have a missional and missionary mindset that is considered fundamental to their purpose.

For this reason, Assyrian monasteries have traditionally incorporated at least one means of outreach and service to the local community where they are planted; traditionally, this has been a library and/or a hospital. Education is highly valued by the Assyrian Church, and a traditional monastic library is akin to a university research library – it is a research and educational centre as well as a library for its own sake.

It is probably for this missional reason that so many Assyrian monasteries are urban in setting. Assyrian monks are expected to serve their local secular community as well as their religious community.

Within the four walls of the cloister, the monks are very disciplined at making space for quiet contemplation, worship, study of the Scriptures, meditation and the inward life of the spirit that characterises the religious calling. However, the Assyrian Church believes that the life of a monastery is as much outside its walls in service to the community as it is inside in inward focus on the Divine. The eremitical tradition is very foreign to Assyrian monastic thought: they are much more often to be found running soup kitchens for the homeless in an inner city, giving instruction in local schools or bringing medical care to the poorest of the poor than as hermits on a mountain top or in the middle of the desert.

Relations with other Churches

The Assyrian Church maintains communion with the Religion of Light church in China, the Church of the East in Bornei and the Thomist churches of India, all of which are nominally independent bodies with their own spiritual leaders. The theology of these churches is broadly similar, however, and each accepts the others' hierarchies and liturgies as valid.

The Church has also begun to take tentative steps towards harmony and eventual reconciliation with the Western Churches (Orthodox and Catholic). As part of this effort, in 1994 the new Catholicos Mar Äbdiyeşü XVII took up an offer by the monks of Mount Athos to send a group of monks to take up residence there in the then-defunct Monastery of the Nativity, as part of an ongoing ecumenical experiment. The Monastery of the Nativity was renamed by the monks the Monastery of Mar Toma (St. Thomas).

Notable People

- Mar Addaıjan II, Metropolitan of Samarqand during the Turkestani War of Independence.

- Mar Äbdiyeşü XVII, Current Catholicos.

- Catholicos Mar Babai the Great, Catholicos 622-647 and prominent Assyrian theologian.

- Mar Bardaysan X, Catholicos 1984-1992

- Qunqasıım Baı, Turkestani wind power developer.

- Mar Zarafan Uldos-ulı, Current Metropolitan of Merv.

- Sultan Qasım-ulı, Current Ilxan of Turkestan.

- Mar Xoch Zaya, Hegumen of the Monastery of St. Thomas, Mount Athos.